7.4.1 Managerial recruitment

Physical Education Teaching

Once the development of a new centre had been agreed, the recruitment of a suitable manager became an immediate priority for local councils and trusts, which had no experience of indoor sports management. Chapter 3 (3.6) referred to the main, early sources of managerial recruitment for sports centre managers. Recruitment sources were varied, though three sectors led the way – physical education, baths management and the military. The variety of managerial backgrounds at the start provide a distinct contrast to the management scene today, where, with longstanding structures now established, managers predominantly rise through the ranks of leisure centre staff, with some coming from other employment.

Through until at least the mid-1980s, physical education teaching proved to be by far the biggest recruiting ground for all management positions, starting from the first appointment (George Torkildsen, who was appointed at Harlow in 1961). PE teachers had completed a three-year, full time course of higher education. Up until the late 1960s a PE teacher’s qualification was the only sport related higher education qualification. Consequently, PE teachers, especially those from the few specialist colleges such as Loughborough, Leeds Carnegie and Exeter St. Luke’s, were to be found in many aspects of sport in this country and abroad. PE teachers were normally the lead person in charge of a school’s sports facilities and equipment. PE teachers were seen to be particularly suited to jobs in sports centre management, especially where public facilities were on school campuses. As we have seen in other chapters, some quite senior military officers also moved into centre management, whilst some council’s entrusted new centres to their existing swimming pool managers. (see Sports Centre Management Recruitment).

7.4.2 Recognition of the need for sound management

There were no specific qualifications for sports centre management, other than the Institute of Baths Management’s technical exams for swimming pools. The need for centre management skills were identified in an early study – “In particular it is the leisure centre manager who needs to possess key qualities of leadership, communication, market awareness, and innovation”.

There were no specific qualifications for sports centre management, other than the Institute of Baths Management’s technical exams for swimming pools. The need for centre management skills were identified in an early study – “In particular it is the leisure centre manager who needs to possess key qualities of leadership, communication, market awareness, and innovation”.

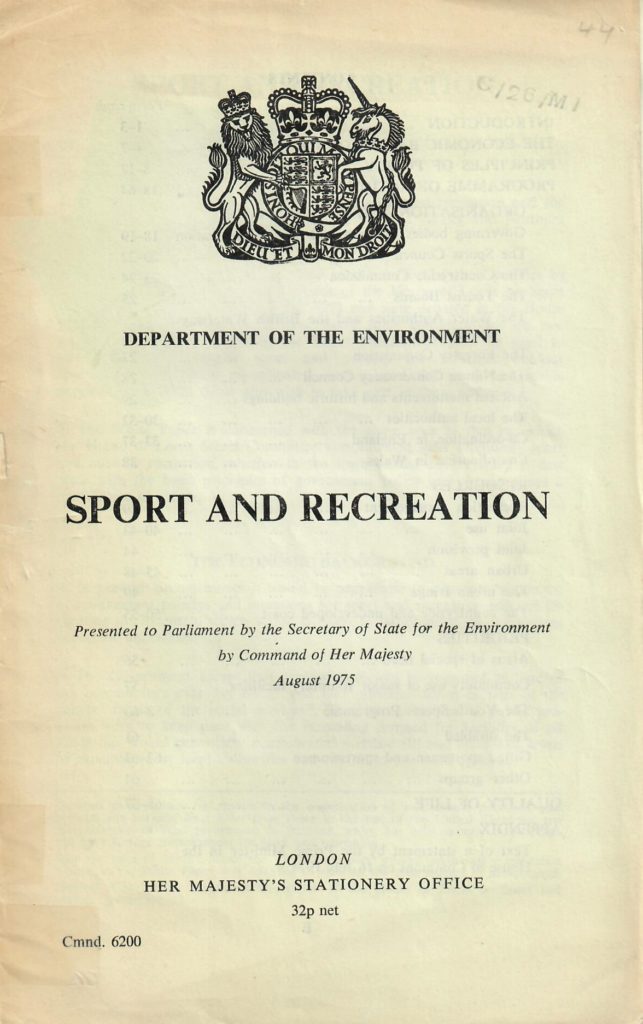

The 1975 Government White Paper, ‘Sport and Recreation’, had also addressed management and career prospects in the evolving sports scene, especially with the arrival of sports centres. To quote the White Paper – “The Government are concerned to improve recreation management with a view to the better use of resources. Employers see a need for improvement of management and career prospects in the recreation field. The Government therefore proposes further consultation with local authority associations and other bodies concerned to set up a study to consider how this may be achieved and to assess the current and future requirements for education and training for managers at various levels – both in the public and the private sector – who are responsible for the day to day running of facilities for sport and outdoor recreation.”

An objective reflection, based on views at that time, was that in terms of management, the early managers were indeed pioneers. Geoff Bott recorded his early thoughts on management whilst at Billingham Forum. They were usually well-educated, intuitive, original, highly motivated and committed to what they were doing. They were largely successful because they made up for their lack of management training and business skills through time, effort and learning through doing. It became apparent, however, particularly with the moves of many of the original managers to posts of seniority in recreation services, that this was not enough. As an indicator of the need for improved management, of the first 70 centres that competed in the Sports Council Management Award in 1976, well over two thirds of them had no written centre objective and no guidelines, other than budget estimates, to measure their performance.

7.4.3 The foundations of training and development

Two academic institutions took an early interest in recreation management and the need for management skills. These were Loughborough University of Technology and North London Polytechnic. The world of academia was, over the coming years, to play an increasing significant part in providing education courses for, and undertaking research into, sports centres and recreation management generally.

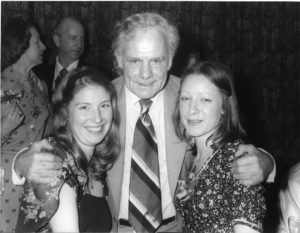

l to r – John Jeffery, Jimmy Munn & George Torkildsen

Under the leadership of John Jeffery, Loughborough UoT launched a Master’s degree course in Recreation Management in 1968/69. In January 1971 it started another course, a Diploma in Recreation Management (see his Training for Recreation Management paper (1972). The Loughborough courses came at an early stage of the development of recreation management and involved a substantial financial and time commitment from the student. Early graduates came from widely differing backgrounds and then went on to enter a whole variety of employments. A few entered sports centres or aspects of recreation management. The courses were ground-breaking and provided a springboard for later developments across the country.

The North London Polytechnic took the longstanding Diploma in Management Studies (DMS) course and created a DMS (Recreation Management). This was the first course to catch the attention of the early centre managers as it was part-time and therefore suited to post-holders. It was perhaps the ‘gold standard’ recreation management course at that time and attracted early managers. Bernard Warden from Bracknell SC presented some lectures. The ordinary DMS and DMS (Public Administration) part-time courses were already established and largely serving industry and government. Several centre managers found these geographically convenient to attend, and the content of the business-based courses and the broad range of attendees beneficial.

In 1983 the first edition of George Torkildsen’s book (‘Leisure and Recreation Management’) with its chapter on Management, Marketing, Performance Appraisal etc. introduced many sports centre managers to management processes as most had not studied the subject.

Over later decades the role of academia in sport and recreation was to grow hugely, both in terms of research and courses ranging from NVQ to degree level. There are now approaching 300 degree-level courses which include the word ‘sport’ in their title and 8,500 students now taking A-Level P.E. across the country! The managers need for accurate and timely information, some of which can be provided by courses and seminars, has been an ongoing issue over the decades (Information Needs of Professionals).

7.4.4 The Yates Committee and Report

Anne Yates CBE JP

As centres developed and recreation departments were formed in local government, attention to the challenges of training and management development grew. The Local Government Training Board undertook a survey in 1974 that highlighted that in the light of recent changes, especially Local Government Re-organisation, existing training patterns and facilities had been overtaken by developments. It also said it awaited the forthcoming White Paper.

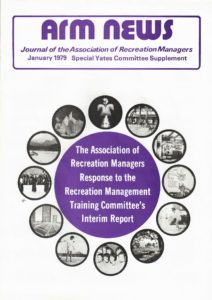

Following on from the White Paper in 1975, The Recreation Management Training Committee, under the Chairmanship of Mrs. Anne Yates C.B.E. J.P, was appointed in 1977 by the Secretaries of State for Education and Science and for the Environment to ‘review and make recommendations on the training of staff and the management of resources and facilities for sport and for all forms of outdoor recreation’. The report was the most comprehensive of its kind yet produced. There was wide consultation across the broad leisure and recreation sector. With the results of the different surveys the committee had commissioned, the report attempted to determine the skills, techniques and areas of knowledge that managers of different levels required and attempted to equate these with the existing network of recreation management courses available. This provided a sound basis for course providers. The main recommendations of the Yates Committee (to which ARM had made a submission) were viewed as evolutionary, not revolutionary and included: –

Following on from the White Paper in 1975, The Recreation Management Training Committee, under the Chairmanship of Mrs. Anne Yates C.B.E. J.P, was appointed in 1977 by the Secretaries of State for Education and Science and for the Environment to ‘review and make recommendations on the training of staff and the management of resources and facilities for sport and for all forms of outdoor recreation’. The report was the most comprehensive of its kind yet produced. There was wide consultation across the broad leisure and recreation sector. With the results of the different surveys the committee had commissioned, the report attempted to determine the skills, techniques and areas of knowledge that managers of different levels required and attempted to equate these with the existing network of recreation management courses available. This provided a sound basis for course providers. The main recommendations of the Yates Committee (to which ARM had made a submission) were viewed as evolutionary, not revolutionary and included: –

- The formation of Regional Training Committees with broad representation. These went ahead but lasted longer in some regions than others.

- A National Council for Leisure. This had been achieved, in a way, in 1975 as the professional institutes had jointly established ‘The National Advisory Council of Leisure Professions’. A National Council for Leisure was not achieved, although efforts for the third recommendation (single institute) tended to over-ride the idea.

- The establishment of a single professional institute for leisure managers.

7.4.5 The existing professional associations

When sports centres first arrived in the 1960s, there were several existing professional institutes and organisations across the broad leisure, sport and recreation scene (see Professional Sports & Recreation Bodies). They were: –

- The Institute of Baths Management (IBM), formed in 1921 as the Association of Baths Superintendents, was a pre-dominant management organisation given its membership across the hundreds and hundreds of UK swimming pools. Subsequently it reflected the changing scene, becoming the Institute of Baths & Recreation Management (IBRM).

- The Institute of Parks and Recreation Administration (IPRA), founded in 1926, represented a very large caucus of parks, grounds maintenance and horticultural staff.

- The Institute of Municipal Entertainment, formed in 1947 as the Institute of Entertainment Managers, which had a significant membership presence in seaside resort councils, especially those with theatres and entertainment centres.

- The Institute of Recreation Management was a small organisation with a number of experienced managers and directors.

- The Recreation Managers Association was founded in 1956 as the Industrial Sports Clubs Secretaries Association.

- The Association of Playing Field Officers founded in 1958. The membership spanned playing field officers in education authorities.

- Other related professional organisations at that time included the Institute of Municipal Catering.

None of these organisations served employees in publicly provided indoor sports facilities, apart from the IBM which did so exclusively for swimming, diving and water polo.

7.4.6 The foundation, growth and success of the Association of Recreation Managers (ARM)

Pre-dating the Yates Committee by seven years was the foundation of the Association of Recreation Managers in 1970. We have seen that the Wolfenden Report in 1960, and other pressures through that decade, together with the roles of the CCPR and Sports Council, plus the re-organisation of local government, were the greatest influences on the provision of the early sports centres. At the same time, the constitution of the Association of Recreation Managers [ARM] in 1970 was one of the most decisive landmarks for the recreation management profession. It was the first professional association rooted in sports centres and its success from 1970 to 1983 is reflected in the various successor organisations, right up to the present day in the form of ‘The Chartered Institute for the Management of Sport and Physical Activity’.

Pre-dating the Yates Committee by seven years was the foundation of the Association of Recreation Managers in 1970. We have seen that the Wolfenden Report in 1960, and other pressures through that decade, together with the roles of the CCPR and Sports Council, plus the re-organisation of local government, were the greatest influences on the provision of the early sports centres. At the same time, the constitution of the Association of Recreation Managers [ARM] in 1970 was one of the most decisive landmarks for the recreation management profession. It was the first professional association rooted in sports centres and its success from 1970 to 1983 is reflected in the various successor organisations, right up to the present day in the form of ‘The Chartered Institute for the Management of Sport and Physical Activity’.

In ‘World Cup’ year, 1966, and with only 6 new public centres built (including Crystal Palace NSC and Harlow), the CCPR had convened a meeting of all those involved in the small number of existing centres and a wider audience from the gathering interest. This led to a series of informal sessions with managers and prospective managers from the developing range of centres and aspirations across the country. In particular, a conference organised in December 1967 at Crystal Palace by the CCPR and Sports Council addressed a range of facility management issues. A symposium for managers was also held at Billingham Forum in 1968. In 1969, with an increasing number of managers meeting in this way, they agreed to form an association. The 25 founding members attended ARM’s first Seminar that year at Afan Lido, Port Talbot. The Association was then formally constituted in February 1970.

As George Torkildsen, a key founding member of ARM wrote, “The formation of ARM stemmed from three sources – the growth of community sports and leisure centres, the first National Recreation Management Conference [at Crystal Palace in 1969] and a series of informal seminars organised by practising centre directors and managers during the late 1960s.” It was a natural progression for managers to meet and discuss emerging ‘best practice’ for this new and exciting concept and visit the newly built facilities.

Research has identified and confirmed some of the earliest members – George Torkildsen, Geoff Bott (1st Chairman), John Williams, Graham Jenkins, Denis Woodman, Bryan ‘Griff’ Jones, Brian Barnes, Bernard Warden, David Thomas, Ian Douglas, Roger Quinton, Barry Stowe and Geoff Gearing and Bryn Thomas were 15 of the 25 founding members confirmed so far. Other early Full Members recorded in the ARM News Archive were: – Jack Fidgett (Crawley SC), Andrew Templeton (Poole SC then Manchester), Peter Forward (Sobell and Waltham Abbey), John Alexander (Bellahouston), John Binks (The Grove, Haverhill, and Bury St. Edmunds), David Reed (Harlow and Poole SC), and Barry Dennis (Stockton YMCA).

- Aims and objectives of ARM

The Association aimed to organise recreation directors and managers in furthering the knowledge of sport, recreation and recreation management. In achieving this the objects of the Association were to:

- secure the advancement and facilitate the acquisition of that knowledge which constitutes the profession of a Recreation Manager.

- represent the interests of Recreation Managers on matters concerning their profession and to maintain and extend the usefulness of the profession for the public advantage.

- maintain relations with other professional associations in related fields.

4 promote the mutual interests of its members.

5 assist with advice on the design, operation and management of recreational facilities.

- Membership eligibility and growth

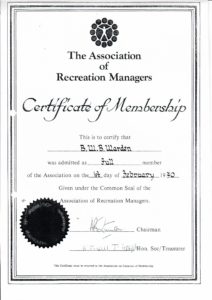

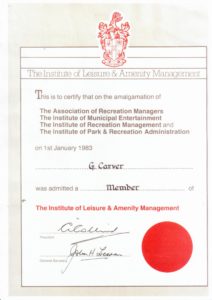

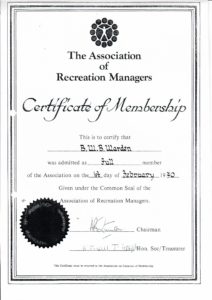

ARM Membership certificate

Membership was of three types (full, associate and student) and was dependent upon the position of responsibility held. At the outset the only criterion for full membership was that the applicant was employed in managing a sports centre. Associate membership was for assistant managers and others such as lecturers and sports council officers.

A National Executive Committee met regularly, and as regional committees were established, regional representatives sat on the Executive. A chairman was elected at the AGM each year, as was a Vice-Chairman who became Chairman the next year. ARM was well served by two successive honorary secretaries in first Pete Saunders (well supported by Assistant Secretary, Doren Pinder), and then Mike Halpin. All the officers and committee members for each year are recorded in the ARM News archive 1970-1983.

The Association made its mark early with the Government. In March 1972, the Association’s Chairman, Vice Chairman, Secretary, and Treasurer were invited to meet Mr. Eldon Griffiths, Junior Minister for Environment and Sport at the Department of in Marsham Street, London. Denis Howell, P.C., M.P., the first Minister of State for Sport and Recreation, was guest of honour and speaker at the ARM Annual Dinner in April 1977 in West Bromwich. He was a keen supporter of ARM.

The Association made its mark early with the Government. In March 1972, the Association’s Chairman, Vice Chairman, Secretary, and Treasurer were invited to meet Mr. Eldon Griffiths, Junior Minister for Environment and Sport at the Department of in Marsham Street, London. Denis Howell, P.C., M.P., the first Minister of State for Sport and Recreation, was guest of honour and speaker at the ARM Annual Dinner in April 1977 in West Bromwich. He was a keen supporter of ARM.

Another keen supporter was Graham Jenkins’ brother, the famous actor Richard Burton, who not only paid for the ARM Chairman’s chain of office but also the first ARM Directory.

As centres burgeoned, ARM attracted nearly all centre managers and assistant managers into its ranks. The growth in its membership was phenomenal, moving from the first 25 members in 1969/70 to 123 in 1972, to over 450 in 1976 (see ARM members 1976) and 705 in 1977, and reaching over 1,000 by 1982, reflecting the growth of centres and recreation management. It quickly broadened its sphere of influence, catering for chief officers, recreation officers within local authorities, managers of swimming pools, trainee managers and students.

- Regional activity across the UK

The rapid expansion was also reflected in the establishment of eleven very active regional branches, based on Sports Council Regions. However, it combined North East England with Scotland as a region. Attendance at these meetings across this region from Teesside to Forfar involved a lot of petrol! These regions had their own committees and organised regular meetings on topics of common interest and enabled the practicing recreation manager to exchange views and discuss problems with fellow managers. At that time, the originality of the sports centre concept and a desire for knowledge meant extremely well attended events, often visiting new facilities. Some regions also held annual golf tournaments.

- An emerging business-like approach

From the mid-1970s the high rate of growth of the sector meant that ARM could exploit, with the expert and committed help of John S Turner & Associates, commercial opportunities such as events, seminars, exhibitions, and annual dinners, where gaining sponsorship was necessary. There was also a weekly mailing service to members. The mailing service was one of the key benefits of membership for ambitious members as many posts were advertised through it, and it was a valuable source of income to the Association. The weekly brown envelope came through the post with the details of at least a dozen new job vacancies, as well as information sheets. Compared with today’s media and technology such a service must seem ‘Jurassic’!

One of the most significant commercial supporters of ARM activity was Ted Blake, who in addition to promoting his sports equipment company, Nissen, was passionate about raising the standards of management in the sector. Nissen sponsored various ARM events over the years.

The Association also extensively explored becoming an advertising sub-agent. A national scheme was considered at length whereby commercial advertising space would be let in participating sports centres on a national contract basis. The legal complexities of such a scheme, involving many local councils, eventually meant that it was not fully practical.

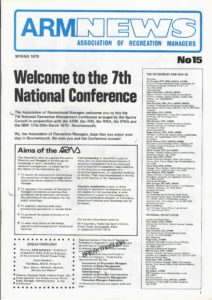

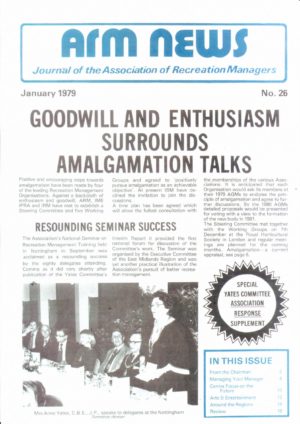

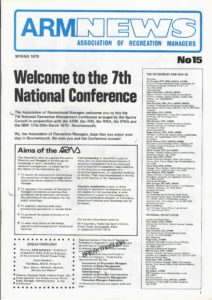

The Association also published a vibrant quarterly newsletter which developed into a highly respected magazine, ARM News (see the full ARM News archive 1970-1983 – this gives a comprehensive picture of ARM’s very active 13-year life, with membership lists, event reports, regional activity, numerous special articles and centres and managers named. The archive represents a veritable treasure trove of practical centre management information and events and views of the period).

The Association also published a vibrant quarterly newsletter which developed into a highly respected magazine, ARM News (see the full ARM News archive 1970-1983 – this gives a comprehensive picture of ARM’s very active 13-year life, with membership lists, event reports, regional activity, numerous special articles and centres and managers named. The archive represents a veritable treasure trove of practical centre management information and events and views of the period).

- Seminars, events, awards and celebrations

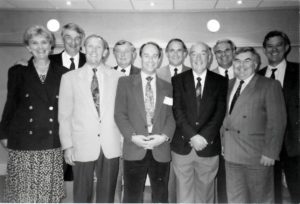

ARM Event

The Association organised Spring and Autumn national seminars in a different part of the country each time. These were very well attended and one of the highlights of the ARM year. In the early days there was also a seminar for ‘2nds and 3rds in command’. After the inaugural seminar at Afan Lido in 1969, seminars were held each year, successively in Afan Lido (again), Broughton, Cardiff, Picketts Lock, Lilleshall, Largs, Chester, Billingham, Home Pierrepoint, Bournemouth, St Austell, Pontypool, Cobham, Nottingham, Sunderland, Saunton Sands, St. Annes, and in 1982, Maidstone. An Annual Dinner was also held each year. In September 1978 ARM organised a National Seminar in Nottingham on Recreation Management Training, which was attended by the Yates Committee Chairman, Anne Yates.

A trophy was awarded to the annual Region of the Year, ARM News had an Award for Article of the Year and there was also an award for a Student Dissertation. An annual national squash tournament for members was held (won, perhaps too many times, by Denis Secher!) and there was even a ‘B***** Awful Golfer Award’ for Bernard Warden!

To celebrate the 10th anniversary of the foundation of ARM a special annual report was published.

By 1981 the Association had bestowed its first fellowships on 22 full members. These had been “members for at least five years, held recreation management responsibilities for ten years and had made a significant contribution to Association affairs”.

- ARM and The Sports Council Management Award

One of the most influential factors in improved management of recreation centres has been The Sports Council Management Award. It was conceived by Ted Blake, initiated by the Facilities Unit of the Sports Council and enabled through sponsorship in its first five years by Nissen International (Sports Equipment) Ltd, and then by Vendepac. ARM supported the Award and provided some of the assessors for both regional and national finals.

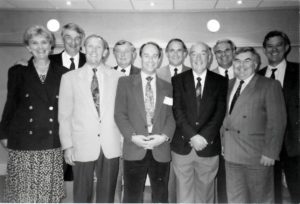

o The people made ARM!

There can be no doubt that ARM was very much a ‘people’ organisation. The early camaraderie amongst members was born of the ‘excitement’ of a new sector with high-profile public buildings. Former PE teachers were to the fore in creating A.R.M. Their outlook on sport and the new challenges of sports centres underpinned the ‘DNA’ of the organisation. Through this story of sports centres, we have recorded the names of numerous people, including many ARM members. However, those recorded are purely representative of the thousands involved in community sports centres across the years. ARM celebrated its 10th Anniversary in 1980.

o ARM – The Conclusion

ARM Reunion 1980s

From 1970 to 1983 the Association of Recreation Managers was the most formidable force in sports centre management, and the development of the recreation management profession. A comprehensive insight into the development, membership and activities is provided by the full ARM News Archive.

- Amalgamation into the Institute of Leisure and Amenity Management (ILAM)

From the beginning ARM recognised the need to increase and widen membership, develop a qualification, seek ‘chartered status’ and raise the status of sports managers in the eyes of other local authority officers. To this end they were proactive in talking to other bodies to seek amalgamation. Initially, in 1980 a Steering Committee (Amalgamation Opportunities) was formed with representatives of five of the existing professional organisations: –

- The Association of Recreation Managers (ARM)

- The Institute of Parks and Recreation Administration (IPRA)

- The Institute of Municipal Entertainment (IME)

- The Institute of Recreation Management (IRM)

- The Institute of Baths and Recreation Management (IBRM)

[Full details – see Professional Sports & Recreation Bodies]

The post-World War II period witnessed an emerging complexity in the relationship between sport and politics in British society (see Chapter 1). Over the period there were cyclical shifts in the political rationale for public investment in sport. The complicated relationship between sport and politics, and sports centres and politics, is rehearsed in a wide range of published books and articles. Ian Henry records in ‘The Politics of Leisure Policy’ (Palgrave, 2001) that “For many years sports centre provision was centre stage with governments and the Sports Council”. Throughout the period there were three predominant issues: a) elite sport b) physical education & school sport and c) community mass-participation. The maturing of the welfare state from 1945 to 1976 had provided very important political underpinning of the original ‘raison d’etre’ for community sports centres. At the original core had been the lack of indoor facilities compared to the rest of Europe, and the UK weather! Chapter 1 explained how various Acts and reports from the mid-1960s to the mid -1970s reflected this gradual maturation. As we saw in Chapter 3 The Wilson Government from 1964 to 1970 was hugely influential, particularly with the 1975 White Paper ‘Sport and Recreation’ and the significant role of Denis Howell MP (1923-1998). Political and cultural decisions taken in the emerging “New Towns” and on Teesside in the mid-1960s and early 1970s to focus on sport and the arts were in fact a pre-cursor for local authorities in the rest of the country.

The post-World War II period witnessed an emerging complexity in the relationship between sport and politics in British society (see Chapter 1). Over the period there were cyclical shifts in the political rationale for public investment in sport. The complicated relationship between sport and politics, and sports centres and politics, is rehearsed in a wide range of published books and articles. Ian Henry records in ‘The Politics of Leisure Policy’ (Palgrave, 2001) that “For many years sports centre provision was centre stage with governments and the Sports Council”. Throughout the period there were three predominant issues: a) elite sport b) physical education & school sport and c) community mass-participation. The maturing of the welfare state from 1945 to 1976 had provided very important political underpinning of the original ‘raison d’etre’ for community sports centres. At the original core had been the lack of indoor facilities compared to the rest of Europe, and the UK weather! Chapter 1 explained how various Acts and reports from the mid-1960s to the mid -1970s reflected this gradual maturation. As we saw in Chapter 3 The Wilson Government from 1964 to 1970 was hugely influential, particularly with the 1975 White Paper ‘Sport and Recreation’ and the significant role of Denis Howell MP (1923-1998). Political and cultural decisions taken in the emerging “New Towns” and on Teesside in the mid-1960s and early 1970s to focus on sport and the arts were in fact a pre-cursor for local authorities in the rest of the country.

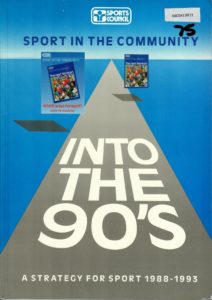

From the mid-1970s Local Government had faced increasing pressure on its services due to social changes ranging from unemployment and poverty to social order problems, especially in the major conurbations. ‘Sport in the Community – Into the 90’s’, the Sports Council Strategy for Sport, published in 1988 highlighted that sport reflected an increasingly polarised society. In the strategy two broad markets were identified as developing at that time: –

From the mid-1970s Local Government had faced increasing pressure on its services due to social changes ranging from unemployment and poverty to social order problems, especially in the major conurbations. ‘Sport in the Community – Into the 90’s’, the Sports Council Strategy for Sport, published in 1988 highlighted that sport reflected an increasingly polarised society. In the strategy two broad markets were identified as developing at that time: –

A raft of Sports Council participation initiatives, including, in 1976, a major national ‘Sport for All’ campaign, and subsequently including an ‘Over 50s’ campaign and ‘Ever Thought of Sport’ for youth.

A raft of Sports Council participation initiatives, including, in 1976, a major national ‘Sport for All’ campaign, and subsequently including an ‘Over 50s’ campaign and ‘Ever Thought of Sport’ for youth.

In fulfilling its statutory brief, The Sports Council’s activity and support for sports centres was extensive and included publishing national planning guidance on facilities, research studies of individual centres, building design guidance as well as ephemeral materials on centre management and construction within its regular publications, “Sport and Recreation” and “Sports Development Bulletin”. The Sports Council’s National Collection, held by the UCLan library in Preston, contains 8,000 books and reports, which ensures that such materials should not be lost for future research. It is an impressive volume and range of material and over 200 relevant items related to sports centres have been extensively reviewed for this Sports Legacy Project.

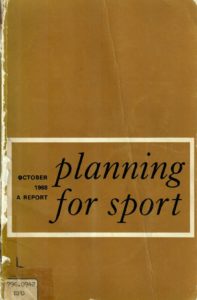

In fulfilling its statutory brief, The Sports Council’s activity and support for sports centres was extensive and included publishing national planning guidance on facilities, research studies of individual centres, building design guidance as well as ephemeral materials on centre management and construction within its regular publications, “Sport and Recreation” and “Sports Development Bulletin”. The Sports Council’s National Collection, held by the UCLan library in Preston, contains 8,000 books and reports, which ensures that such materials should not be lost for future research. It is an impressive volume and range of material and over 200 relevant items related to sports centres have been extensively reviewed for this Sports Legacy Project. The first national facilities planning advice was published by the advisory Sports Council in the publication “Planning for Sport” (1968) and the Sports Council adopted this policy framework when it became an executive body in 1972. It also took over the majority of the staff of the CCPR so the task of implementation fell to the Council’s National Facilities Unit and its regional counterparts.

The first national facilities planning advice was published by the advisory Sports Council in the publication “Planning for Sport” (1968) and the Sports Council adopted this policy framework when it became an executive body in 1972. It also took over the majority of the staff of the CCPR so the task of implementation fell to the Council’s National Facilities Unit and its regional counterparts. Details of “Planning for Sport”, “Provision for Sport”(1972) and “Sports Halls; a new Approach to their Dimensions and Use,” (1975) the Council’s main national strategic documents of the period in relation to sports centres are covered in Chapter 4, and in Mike Fitzjohn and Malcolm Tungatt’s detailed sections In Chapter 4 and 9 on

Details of “Planning for Sport”, “Provision for Sport”(1972) and “Sports Halls; a new Approach to their Dimensions and Use,” (1975) the Council’s main national strategic documents of the period in relation to sports centres are covered in Chapter 4, and in Mike Fitzjohn and Malcolm Tungatt’s detailed sections In Chapter 4 and 9 on  The development of facility planning guidance based on empirical research enabled the Council’s officers in its 9 regions to use their influence through the Regional Sports Councils and subsequently the Regional Councils for Sport and Recreation, and their contacts with Local Authorities, to promote rationally planned facility provision for the benefit of local communities. It is often postulated that the surge in the provision of sports centres in the period 1974 – 78 was largely due to the impact of the 1974 reorganisation of local government (see Chapter 3.) However, the availability of planning, research and design advice from the Sports Council and the lobbying of its regional officers ensured that sport was at the forefront of the minds of prospective providers during this period. It is often overlooked that other forms of public leisure facilities in the arts, libraries and heritage sectors for example, lacking such well-developed plans and advocacy networks, did not experience anything like the scale of growth as that seen in sports provision during the same period.

The development of facility planning guidance based on empirical research enabled the Council’s officers in its 9 regions to use their influence through the Regional Sports Councils and subsequently the Regional Councils for Sport and Recreation, and their contacts with Local Authorities, to promote rationally planned facility provision for the benefit of local communities. It is often postulated that the surge in the provision of sports centres in the period 1974 – 78 was largely due to the impact of the 1974 reorganisation of local government (see Chapter 3.) However, the availability of planning, research and design advice from the Sports Council and the lobbying of its regional officers ensured that sport was at the forefront of the minds of prospective providers during this period. It is often overlooked that other forms of public leisure facilities in the arts, libraries and heritage sectors for example, lacking such well-developed plans and advocacy networks, did not experience anything like the scale of growth as that seen in sports provision during the same period. If the Council’s influence in funding sports buildings was limited, its impact on their design was significantly greater. The Technical Unit for Sport (TUS) was a group of architects, engineers, quantity surveyors and other building professionals under the leadership of

If the Council’s influence in funding sports buildings was limited, its impact on their design was significantly greater. The Technical Unit for Sport (TUS) was a group of architects, engineers, quantity surveyors and other building professionals under the leadership of

Following an early meeting of centre managers and interested parties at Crystal Palace NSC in the late 1960s, a professional body essentially for managers, the Association of Recreation Managers, was formed in 1969 and formalised in 1970 (see 7.4). Harry Littlewood helped with support and advice. Rec Man with its prestige reinforced the importance of such professional development. Harry also introduced The

Following an early meeting of centre managers and interested parties at Crystal Palace NSC in the late 1960s, a professional body essentially for managers, the Association of Recreation Managers, was formed in 1969 and formalised in 1970 (see 7.4). Harry Littlewood helped with support and advice. Rec Man with its prestige reinforced the importance of such professional development. Harry also introduced The  The Council inherited from the CCPR five National Sports Centres at Bisham Abbey in Buckinghamshire; Lilleshall in Shropshire; Crystal Palace in London; Cowes Sailing Centre on the Isle of Wight and Plas-y-Brenin Mountain Centre in Snowdonia. It later added a National Water Sports Centre at Holme Pierrepont in Nottinghamshire. Although the primary purpose of the National Centres was to provide training and competition venues for National Governing Bodies of Sport, both Crystal Palace and Holme Pierrepont were extensively used by their local communities, particularly schools. John Birch, former Director of Regional Services of the Sports Council, has set out the role and development of the

The Council inherited from the CCPR five National Sports Centres at Bisham Abbey in Buckinghamshire; Lilleshall in Shropshire; Crystal Palace in London; Cowes Sailing Centre on the Isle of Wight and Plas-y-Brenin Mountain Centre in Snowdonia. It later added a National Water Sports Centre at Holme Pierrepont in Nottinghamshire. Although the primary purpose of the National Centres was to provide training and competition venues for National Governing Bodies of Sport, both Crystal Palace and Holme Pierrepont were extensively used by their local communities, particularly schools. John Birch, former Director of Regional Services of the Sports Council, has set out the role and development of the

which later became UK Sport. The “community function” was passed to the new “English Sports Council” with similar bodies in the other home countries. In 1997 the English Sports Council adopted the new ‘brand name’ of “Sport England” which has assumed the role of developing sport in England over the last twenty years. However, despite its various changes of name and role, one lasting legacy of the Sports Council to centres has been the universal adoption of its “Sport for All” logo as the definitive direction and access sign for sports centres.

which later became UK Sport. The “community function” was passed to the new “English Sports Council” with similar bodies in the other home countries. In 1997 the English Sports Council adopted the new ‘brand name’ of “Sport England” which has assumed the role of developing sport in England over the last twenty years. However, despite its various changes of name and role, one lasting legacy of the Sports Council to centres has been the universal adoption of its “Sport for All” logo as the definitive direction and access sign for sports centres. As we have seen in the previous section, the Sports Council changed its name and role on several occasions. However, the most profound change and the greatest impact on the culture and the performance of our national sporting agency came about with the advent of the National Lottery Sports Fund.

As we have seen in the previous section, the Sports Council changed its name and role on several occasions. However, the most profound change and the greatest impact on the culture and the performance of our national sporting agency came about with the advent of the National Lottery Sports Fund.

In the early days of the Fund a lot of significant strategic projects were supported in the major cities, and rural market towns. This then trended into more support for projects on education sites, particularly Specialist Sports Colleges offering curricular, extra-curricular and community use on either a casual or booked basis.

In the early days of the Fund a lot of significant strategic projects were supported in the major cities, and rural market towns. This then trended into more support for projects on education sites, particularly Specialist Sports Colleges offering curricular, extra-curricular and community use on either a casual or booked basis. Based on figures provided by the distributors and assuming that the Lottery to project cost ratio is similar for Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales as for that in England, it is an estimate that the Lottery has generated over two billion pounds worth of investment in about 800 sports centre projects in the U.K over the 25 year period from 1994 to 2019 – a significant and historic investment and one which would probably not have been made without the vision of political and sporting leaders at that time of the conception of the Lottery.

Based on figures provided by the distributors and assuming that the Lottery to project cost ratio is similar for Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales as for that in England, it is an estimate that the Lottery has generated over two billion pounds worth of investment in about 800 sports centre projects in the U.K over the 25 year period from 1994 to 2019 – a significant and historic investment and one which would probably not have been made without the vision of political and sporting leaders at that time of the conception of the Lottery.

There were no specific qualifications for sports centre management, other than the Institute of Baths Management’s technical exams for swimming pools. The need for centre management skills were identified in an early study – “In particular it is the leisure centre manager who needs to possess key qualities of leadership, communication, market awareness, and innovation”.

There were no specific qualifications for sports centre management, other than the Institute of Baths Management’s technical exams for swimming pools. The need for centre management skills were identified in an early study – “In particular it is the leisure centre manager who needs to possess key qualities of leadership, communication, market awareness, and innovation”.

Following on from the White Paper in 1975, The Recreation Management Training Committee, under the Chairmanship of Mrs. Anne Yates C.B.E. J.P, was appointed in 1977 by the Secretaries of State for Education and Science and for the Environment to ‘review and make recommendations on the training of staff and the management of resources and facilities for sport and for all forms of outdoor recreation’. The report was the most comprehensive of its kind yet produced. There was wide consultation across the broad leisure and recreation sector. With the results of the different surveys the committee had commissioned, the report attempted to determine the skills, techniques and areas of knowledge that managers of different levels required and attempted to equate these with the existing network of recreation management courses available. This provided a sound basis for course providers. The main recommendations of the Yates Committee (to which ARM had made a submission) were viewed as evolutionary, not revolutionary and included: –

Following on from the White Paper in 1975, The Recreation Management Training Committee, under the Chairmanship of Mrs. Anne Yates C.B.E. J.P, was appointed in 1977 by the Secretaries of State for Education and Science and for the Environment to ‘review and make recommendations on the training of staff and the management of resources and facilities for sport and for all forms of outdoor recreation’. The report was the most comprehensive of its kind yet produced. There was wide consultation across the broad leisure and recreation sector. With the results of the different surveys the committee had commissioned, the report attempted to determine the skills, techniques and areas of knowledge that managers of different levels required and attempted to equate these with the existing network of recreation management courses available. This provided a sound basis for course providers. The main recommendations of the Yates Committee (to which ARM had made a submission) were viewed as evolutionary, not revolutionary and included: –