In the 1945-1964 period, as before the war, there was no government ‘sport’ policy as such. The national organisations most concerned with sport until the early 1960s were the Central Council for Physical Recreation (CCPR), now Sport & Recreation Alliance, and the National Playing Fields Association (NPFA). In 1957, the CCPR appointed a small independent committee, under the chairmanship of Sir John Wolfenden, Vice-Chancellor of Reading University, to examine the general position of sport in this country and recommend what action should be taken by statutory and voluntary bodies if games, sports, and outdoor activities were to play their full part in promoting the general welfare of the community. The CCPR worked in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, but with the support of the Scottish Council for Physical Recreation, the inquiry covered the whole of the United Kingdom. Though not a government review, it was taken by all as the most significant study to date of the national sports scene.

Post-war social thinking and developments through the 1950s provided a generally favourable climate for new sports centres. There was a need for sports halls to accommodate the burgeoning indoor sports (volleyball, basketball, badminton, indoor tennis, and handball) which were being encouraged by the CCPR at that time (and later by the Sports Council). However, it took the Wolfenden Report to start to shake the ground regarding sport and facility provision. There had not previously been any similar case for sport. There had been a slow acceptance of the benefits of recreation, but the argument for parliamentary recognition did not get underway until the Wolfenden Report in 1960. Whilst it was eventually to have a big influence on government thinking and support for sport, the initiative came from the CCPR. The Wolfenden Committee was appointed by the CCPR in October 1957 with the following terms of reference – “To examine the factors affecting the development of games, sports and outdoor activities in the United Kingdom and to make recommendations to the Central Council of Physical Recreation (CCPR) as to any practical measures which should be taken by statutory or voluntary bodies in order that these activities may play their full part in promoting the general welfare of the community”.

Jack Longland The climber

Recognisable names from that era on the Wolfenden Committee included Jack (later Sir Jack) Longland (1905-1993) mountaineer, educationalist, broadcaster, and Vice-Chairman of the Sports Council 1966-74; and of course, David Munrow. Justin Evans MBE, Deputy Secretary of the CCPR, was secretary to the Committee. The greatest credit went to the Chairman, Sir John Wolfenden CBE (1906-1985), later Baron Wolfenden, whose chairing of the Committee and its processes was considered commendable.

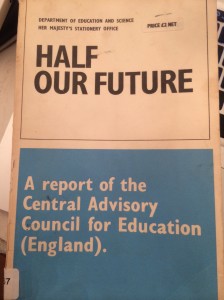

The committee held its first meeting in January 1958 and its working methods did much to enhance its status. In two years, it took evidence from hundreds of individuals and organisations, including all the major sports bodies. The Report of the Wolfenden Committee on Sport – ‘Sport & the Community’ was published in 1960 and became a benchmark for sport and community sports provision. Whilst the Wolfenden Committee was mainly concerned with physical recreation outside of school, the Wolfenden Report was to sit alongside or preface a range of other major reviews around that time into sporting, educational and social issues. One of its major proposals was to establish an independent “Sports Development Council” to oversee government policy on sport and to promote sport more widely.

The Wolfenden Report was formally launched at a press conference in London on September 28th, 1960. Sir John was already conscious of concerns regarding the proposal to introduce a Sports Development Council. The Report was warmly welcomed by all sports enthusiasts. The first print run of 10,000 copies quickly ran out and 5,000 further copies were printed. It was widely reported favourably by numerous national publications including the Guardian, Daily Herald, Sunday Dispatch, Daily Telegraph, and Daily Mail.

The special factors and problems examined by the Wolfenden Committee included the gap in the levels of participation in sport between school years and post school lives (this became ubiquitously known as the ‘Wolfenden Gap’). Facilities, coaching, organisation, administration and finance, amateurism, international sport, the press, television and radio, and Sunday games were also covered by this far-reaching report. There was a public perception that that there was lack of interest in sport on the part of the relevant government department at that time, the Ministry of Education, which had handled any grants arising from the 1937 Act.

Wolfenden made a total of 57 recommendations across its brief. The two headline recommendations for the development of sport were: –

- For the creation of a Sports Development Council to provide the basis for a constructive new approach to assessing appropriate provision for community sports grounds, swimming pools, sports halls, and other indoor facilities.

- To furnish the new Council with finance.

Wolfenden not only recommended the establishment of a Sports Development Council but £5 million as the amount to be distributed in any one year. A figure of £5 million was also recommended as an annual sum to be sanctioned over and above existing permissions for capital expenditure by statutory bodies. The recommendation for a Sports Development Council proved to be the most contentious issue politically. For example, Phyllis Colson, the founder of the CCPR which had set up the Wolfenden Committee, lobbied aggressively against it, which in part explained the delay in implementing the proposal. It was not until after the retirement of Miss Colson and the appointment of Walter Winterbottom as her successor that any progress was made.

Specific recommendations related to indoor sports provision were: –

- “More swimming baths are urgently needed. As a general rule, these should be indoor.”

- “The most serious shortage of facilities is that for indoor games and sports. This can only be met by the action of local authorities or local education authorities. The erection of large barns would provide for many needs.

- The establishment of experimental multi-sports centres is recommended. The initiative in establishing them must come in the main from local authorities and local education authorities.

Leicester Sports Hall Barn

The term ‘barn’ may seem somewhat rustic in the context of sports hall development over the subsequent 56 years. However open-sided barn-type structures were developed in some places, particularly in Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire. One project supporter taught in such a sports hall at Ibstock Penistone School, Leicestershire. Wolfenden also emphasised the important role of local authorities and education authorities. It also addressed the issue of multi-sports centres that combined both indoor and outdoor facilities. The report saw advantages in such joint indoor and outdoor provision for social and family benefits. Wolfenden noted that such centres were common abroad and that plans were progressing for

Gosling early development work

such a centre at Harlow. However, as history reveals, such centres did not become common-place, not least because existing outdoor sites were not usually chosen for new indoor centres, which were often built on smaller sites nearer town centres. The exceptions were joint provision centres on school sites with playing fields. Nonetheless there are some excellent indoor/outdoor examples, not least Gosling Park at Welwyn Garden City, which first opened as an outdoor centre in 1959. A sports hall was not added until 1976. Wolfenden also raised the issue of local authorities combining to provide sports centres. This was a concept that did not take-off, not least because parochial attitudes prevailed.