9.4.5 The overall principles and key step for a new centre in the 21st Century

Apart from schools, a new leisure centre for a town or area is now probably the biggest and most prestigious building a Local Authority can procure. The role and scope of Local Authorities today, under government financial controls, means that it is also one of the few large complexes an Authority can commission itself.

The new centres developed and being planned in the 21st century are generally based on five key principles to: –

- provide new buildings and, if required, replace old centres that do not meet modern building sustainability and economic priorities or demographic change

- achieve lower revenue costs from well designed, well targeted and well-used facilities under revised management contracts, based on sound business plans for revenue streams.

- continue to provide opportunities to meet modern and changing leisure and recreation interests. The local leisure centre is perhaps seen as essential as a mobile phone in the modern world.

- give opportunities to encourage physical activity for a healthy lifestyle and to potentially take the opportunity to blend the recreation facilities with other community services.

- meet statutory requirements for Health and Safety and Accessibility. The 21st century also demands environmentally sustainable development which requires an overall approach that is pervasive throughout the development process.

From the initiation of the process by a Local Authority, the following steps show the broad development pathway that is taken. Not all authorities adopt the same pathway, but all largely reflect the key steps.

The five key steps of the process, which are underpinned by the five key principles above, normally go – from –

a) A feasibility study, including the business plan (as revenue drives the brief and shapes projected local demand thus avoiding an over-scaled project) and which may also initially involve an overall strategic review of facility provision in the area – to

b) The brief itself, which is particularly important politically and for the architect, reflecting user and owner/operator needs – to

c) The architect led masterplan embracing site/location and environmental issues – to

d) The detailed architectural design in accordance with RIBA and statutory standards and any public consultation – and this then leads on to

e) Seeking planning permission (see Alton Sports Centre example) and –

f) commissioning the construction (unless a design & build route has been chosen). This stage may partially overlap with the architectural design, depending on the format and timing of contractor procurement, and the centre experience of some contractors to contribute to final design detail.

9.4.6 New centres for old?

Billingham Forum

Where existing, longstanding centres are part of a strategic review of the area or a feasibility study, one challenge is whether to build new or refurbish. The last twenty years has been dominated by the huge number of older centres in need of replacement or major refurbishment. The extensive refurbishment of Billingham Forum, which opened in 1967, was a successful project undertaken from 2009 to 2011, and carried out at a cost of £18.5M.

Looking at new centres in this century (fully explored in Chapter 10), a vast number of centre projects have been directly linked to the desire to replace ‘old, worn out’ centres dating back to the 1970s and 1980s. In many cases a project has started out asking the question – do we plan for a new centre(s) or do we refurbish? One consideration has been that some refurbishments of 1970s centres have not stood the test of durability in a fairly short time. There have been examples of the refurbishment route successfully being chosen for financial and/or practical reasons. Fairfield Pool and Leisure Centre in Dartford was over 40 years old and between 2014 and 2016 it was completely refurbished by taking it back to its concrete frame and extended with a new

Swansea LC2

sports hall. At £12M this was a much lower cost than a completely new building. Swansea Leisure Centre (see Chapter 10) was officially opened by the Queen in 1977 but was deemed unsafe in 2003 and closed amid much political argument. After much debate about the building and the task of refurbishment, it was virtually gutted and the shell completely refitted at a cost of up to £32M, re-branded as LC2 and re-opened by the Queen in 2008. Perhaps the only centre to be opened twice by Her Majesty!

Given the poor state of many existing centres, a far greater proportion of Local Authorities have opted for replacement with a new centre, often situated at a new location within a revised and rationalised district-wide plan and a revised management contract. One new centre that has achieved significant revenue savings is Westminster Lodge Leisure Centre in St. Albans, where substantial annual savings approaching £1M have been claimed. Refurbishment of Tewkesbury Leisure Centre at £3.8M was not viewed as value for money against the new centre that went ahead for £8M and also removed a £148,000 revenue subsidy. Oldham Council invested in two new centres to replace four old buildings, reducing annual net operating costs from £1.7M to £400,000. The vast Spectrum in Guildford (1993) is an example of a centre that suffered early from technical issues, especially with its roof. Consequently, its replacement became an issue by the early part of the 21st century (see Chapter 10).

A new building has all the advantages of a new design and modern technology. Time will tell if the new centres have greater durability and longevity than their predecessors.

9.4.7 How has design changed and developed from the mid-1990s until 2020

- Swimming pool and sports trends

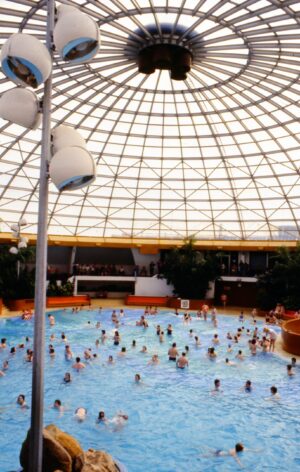

A significant change since the mid-1990s has been the sharp decline, almost to zero now, in the provision of new leisure pools. There is no doubt leisure pools are great for families ‘messing about in water’ but there is now an emphasis on traditional swimming pool provision. This is due to the increased use and value of conventional lane pools for health and fitness swimming; competitive swimming demands; the spatial flexibility afforded by ‘boom dividers’ and moveable floors in traditional pools to create smaller spaces for lessons; and the higher staffing costs for leisure pools. There have not been any ‘mega-sized’ centres as was seen in the 1970s and 1980s when a few large centres were developed with grand leisure facility aspirations. These centres were usually built with insufficient regard for revenue costs, especially the staffing needs to operate the centres successfully. For example, from 1977, Crowtree had over 200 hundred staff on the payroll (145 full-time equivalent).

Sports hall provision has also declined in importance with far fewer large eight-badminton court sports halls (except for universities) and many more of four-badminton court size. Some of this may be due to the growth of outdoor 5-a-side football on floodlit artificial surfaces, as opposed to indoor, which previously tended to dominate sports halls. Additionally, the growth since the 1990s of other specialist event venues has been significant. New sports and leisure centres do not have the space or budget to provide and store the demountable seating that facilitated many major events at centres until the 1990s. New bowls hall provision is limited, squeezed by some indoor clubs building their own facilities and paradoxically, for the majority user age group, lower indoor bowls participation in some areas.

Go Climb

Design has also been led by provision for new popular activities of the age, such as indoor climbing and other attractive ‘adventure’ activities. These include climbing experiences at Crawley’s K2 (2005) where the prominent climbing wall in the large foyer lent itself to the Centre’s modern name. The substantial ‘Go Climb’ experience at the refurbished Billingham Forum saw an

Adrenaline Centre

end to the sports hall, and the 1970s’ Haslingden Sports Centre, marketed now as the ‘Adrenaline Centre’ and aimed at family groups, includes ‘Grip and Go’ climbing and laser tag. In 2019 Harlow Leisurezone (2010) converted its large tennis hall to a huge new Urban Limitz Adventure Trampoline Park (see also Chapter 10 for new trends).

9.4.8 New priorities and arrangements come to bear

New centre developments have taken place despite economic pressures on local government, especially during the decade of financial austerity from 2009. Up to 2020 this has helped to create a vibrant architectural design and construction market for centres. Operational management input to design has changed too, from the role of the early appointed individual centre manager up to around the 1990s, to input now from the designated operator organisation. Increasingly that input is made at an early stage, and throughout the design process. An imperative for the design of some new centres has been the move to broaden the role of the centre. This can include health and well-being priorities and community services, such as a library or a GP practice, creating new design concepts and perhaps influencing locations (see Chapter 10).

As nearly all centres are now managed on a quasi-commercial basis by trusts (local, regional or national – see Chapter 8) the operational management contracts with them, which have been negotiated or re-negotiated as part of ‘new centre’ development deals, have underpinned the large number of centres commissioned in the last 20 years. One concern is that as Local Authority budgets have continued to be squeezed, socially inclusive use of centres might be too easily over-ridden by the need to increase income and improve financial performance.

K2 Crawley

The ‘fitness boom’ of the 1990s has had a significant impact on the design process for public facility provision in the 21st century. The advances in the private gym sector challenged local authorities to provide commercial standard gyms and group activities for members. Gym membership has become part of everyday life for many. Schemes such as that at K2 in Crawley in 2007 saw the gym placed at the forefront of the scheme in a light airy and visible position to attract the public. Space and Place’s large Littlehampton Wave gym on the first floor is highly visible from the outside, with large glass windows providing users with a panoramic view overlooking the seafront and English Channel. The design motto has become ‘accessible sport for all, not closed boxes’.

9.4.9 Technology plays a big part

Design and installation details principally evolve from conceptual ideas for a new age and technical advancements. Some of the most radical changes over the years have been related to technical plant, in particular for swimming pools and more generally across the building in terms of heating, lighting and ventilation. In the case of swimming pools, the visual impact is now far removed from the public baths and pools scene, particularly pre-1970, when pool halls often resembled the flooded downstairs of a hospital! Technological advances in relation to energy conservation, temperature controls, rooms to room (where again guidance is published by Sport England), and minimising maintenance costs have been extremely important. Sustainability has become a watchword for design and construction and the Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) is the world’s leading sustainability assessment method for master-planning projects, infrastructure and buildings. It recognises and reflects the value in higher performing assets across the built environment lifecycle, from new construction to refurbishment.

Two new centres provide examples of new standards and procedures. The Ebbw Vale Sports Centre, a key part of the town centre’s regeneration, provides a 25-metre, six-lane swimming pool with viewing gallery, fun pool with slides, fitness suite, weights room, cafeteria and a six badminton-court sports hall with seating. Designed by BDP, it has been built by Willmott Dixon to a BREEAM Excellent standard. St Sidwell’s Point, Exeter’s new leisure centre, designed by Gale & Snowden Architects in conjunction with Space & Place, is set to open in the Summer of 2022. It is the Council’s flagship in the city centre regeneration masterplan. It is a pioneering £44M Leisure Centre and is aiming for Passivhaus certification for the swimming pool to become a world first for a leisure centre (Passivhaus is the leading international low energy, design standard). Brighouse and Sowerby leisure centres for Calderdale Council are being built not only to BREEAM standards but also to WRAP’s Designing out Waste process. Bluetooth beacons are another modern development for centre technology. Bluetooth beacons are hardware transmitters that enable smartphones, tablets and other devices to perform actions when near the beacon.

performance relative to national benchmarks. Sports and Leisure Centres can choose from: a full report – assessing access, utilisation, finance and customer satisfaction; an Efficiency Report – assessing finance and utilisation performance; or an Effectiveness Report, which takes access, utilisation and customer satisfaction into consideration. A one-page Executive Summary also ensures the reports are clear and easy to understand!

performance relative to national benchmarks. Sports and Leisure Centres can choose from: a full report – assessing access, utilisation, finance and customer satisfaction; an Efficiency Report – assessing finance and utilisation performance; or an Effectiveness Report, which takes access, utilisation and customer satisfaction into consideration. A one-page Executive Summary also ensures the reports are clear and easy to understand!

of provision, indoors and outdoors, and was supplemented by a separate report commissioned to review three of Brent’s Sports Centres (Bridge Park, Charteris and Vale Farm) and offer a best-fit solution for future provision. Across the wide sports centre scene the quantity, quality, accessibility and demand of facilities was assessed. It highlighted there had been little investment in the Borough’s sporting infrastructure over the previous twenty years. The strategy sought to ensure a planned approach for provision in the future to match the existing and growing need of the community.

of provision, indoors and outdoors, and was supplemented by a separate report commissioned to review three of Brent’s Sports Centres (Bridge Park, Charteris and Vale Farm) and offer a best-fit solution for future provision. Across the wide sports centre scene the quantity, quality, accessibility and demand of facilities was assessed. It highlighted there had been little investment in the Borough’s sporting infrastructure over the previous twenty years. The strategy sought to ensure a planned approach for provision in the future to match the existing and growing need of the community.