In parallel with and following those first school and university initiatives, progress can be logged through the mixture of approaches taken to design and provision (as outlined in 4.1.1) and the principal issues identified through the following series of events and initiatives. These were some of the key design and provision ‘benchmarks’ of the period.

1) Designing the first centre: Harlow 1959-1969

In the 1960s the design of the Harlow sports hall had been initially entrusted to the architect Sir Frederick Gibberd, the independent architect working on the wider Harlow New Town development. Gibberd donated his services for the Sportscentre free, such was the Harlow Trust’s battle for finance to build the sports hall. Gerry Perrin was Harlow New Town’s in-house architect in 1958/59. Perrin worked with Gibberd on the design of Harlow’s sports hall and became one of the earliest pioneering sports centre architects. Perrin’s early involvement in the planning and design of that very first centre led to him being awarded, in 1962, a Fellowship by the NPFA and CCPR, in conjunction with the Polytechnic (Regent Street) School of Architecture. The Fellowship was aimed at carrying out and coordinating research on the planning, design and construction of sports halls and pavilions. The report, ‘Community Sports Halls’ was published, with much technical detail, by the NPFA in 1965 (price – one guinea!). This was the first ‘bible’ of centre design and an invaluable compendium based on the very early research and experiences. It was revised in 1971.

The archived Harlow Trust correspondence shows that in 1963 the construction cost quoted for the sports hall was £118,187, with George Wimpey undertaking the main construction at cost. This gesture also reflected the battle the Harlow Trust had over 3 years to fund the sports hall building with grants from a range of different sources.

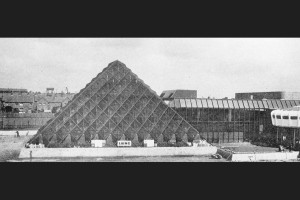

Harlow Sports Hall

The construction of a ‘simple box’ as a main sports hall (120’ x 100’ x 28’) within budget was the basis of the Harlow design, alongside a flexibility suited to a range of sporting activities. It was considered important to provide a reasonable internal playing environment suitable for most of the main activities accommodated. Smooth-faced grey brick walls and a semi-sprung maple wood strip floor were well-liked by the majority of users. The combination of woodwork (acoustic) ceiling and high-level galleries around the hall, gave a satisfactory reverberation time for both coaching instruction, and spectator comfort during noisier games. Warmed air (50-55oF) was blown down side walls by means of industrial heating units operating from an oil-fired boiler. Two large roof-mounted extract fans gave one complete air-change per hour. The design also enabled 8 badminton courts to be converted to space for trampolining and gymnastics in 10 minutes. Netting to define playing areas, plastic tape for court markings and bleacher moveable seat units were part of the sports hall picture.

The Harlow sports hall was so successful that by 1969 plans were underway for extending the size of the sports hall and the extension came into operation in January 1970. Some adaptations were made, such as a suspended ceiling to eliminate a poor background contrast of the roof area. Harlow’s sports hall was ground-breaking for the UK at that time, and a template had been set for the first centres. It had a basic design, layout, format and regime that would remain, in essence, familiar to most centres over the following half century. It is difficult in the 21st century to imagine the very limited knowledge and design experience that was around at that time as new centres were planned.

2) Pioneering architects and first design developments

Dunstable Sports Centre

Initially, a small number of pioneering architects, including Gerry Perrin and some Local Authority architects, greatly influenced the first designs. Subsequently, in private practice, Perrin’s work included the design of Folkestone Sports Centre in 1972 (on a difficult sloping site), Dunstable Sports Centre, noted for its irregular shaped pool incorporating standard 25m lanes, and Newbury Sports Centre. [Perrin’s involvement as a Fellow and as a sports centre architect led to publication of his two standard texts – ‘Sports Halls and Swimming Pools’ published in 1980 by Spon, and ‘Design for Sport’ published in 1981 by Butterworth].

The Crystal Palace National Sports Centre, which mirrored Harlow’s timing in 1964, was designed by London County Council’s architects, led by Sir Leslie Martin and George Finch. Indeed, the design of a sports centre was so new to the architectural scene that many local authority architect departments, at that time well established and staffed, took on the task of designing the ‘local’ sports centre. As mentioned previously, the first centres were inundated with visiting local council delegations, which included in-house architects with their local brief to fulfil. “If it’s going to be built in our area, we should design it” was a prevalent sentiment, probably alongside considerations of cost and professional pride. Advice however was also taken from the TUS and the private architects involved in the first centres.

Other early architectural credits in this pioneering period included Elder Lester Architects (Billingham Forum); John Rice, who designed Bracknell Sports Centre (and went on to design Ashford Sports Centre), Corporation of Glasgow (Bellahouston) Faulkner-Brown, Hendy, Watkinson, Stonor (Lightfoot Centre), Williamson Partnership (Deeside) and Arthur Gomez (Farnham Sports Centre).

This pioneering period led on to the rapid development of centres in the 1970s, with both Local Authority and private architects coping with the expansion, with some specialist sports & leisure architects emerging in the decade.

3) NPFA Symposium on Sports Centres: The College of Architecture – The Polytechnic, London February 1969

Historic Record

In February 1969 the first review and significant benchmark – a symposium – was held for the design and building of sports centres. The event was organised jointly by the NPFA and The Polytechnic (Regent Street) College of Architecture & Advanced Building Technology. A presentation was made by Gerry Perrin. Discussion groups were chaired by Harry Faulkner-Brown (Sports Halls); P. Lusher (Swimming Pools) and George Torkildsen (Sports Hall Management).

Perrin presented on centre design and planning with particular reference to sports centres and halls open or under construction at that time. Perrin referred to the early centres of Bracknell, Crystal Palace, Ponteland, Stockton, Billingham, Birmingham University, Bingham, Folkestone, and of course Harlow. Location, he stated, is a big factor in the external design of a centre. Perrin highlighted the various types of locations so far chosen, quoting the examples of town centre (Poole, Basingstoke and Billingham); town periphery (Harlow and Folkestone); sub-regional (Lee Valley) and joint use developments on school sites (Nottinghamshire). Early technical issues identified included sports hall glazing, heating and flooring. He quoted the University of Kent sports hall at Canterbury, which had walls of honey coloured sand-lime brick, as, overall, the most technically correct at that time. At that time, even the preferred size of sports hall was under discussion. Some early indicators for the scale of provision for the size population were also presented. Consideration was given to the advantages and disadvantages of a 1-court sports hall (1 basketball court) over a 2-court hall, although Faulkner-Brown argued a 1 court hall was considered limiting in terms of usage. The capital cost/revenue income ratio was also a consideration but, at that time, clear conclusions were not however drawn on the issue. With a limited number of centres at that time, capital cost was a key focus, with detailed building costs analysed by The Polytechnic based on the Kent University sports hall.

Harry Faulkner-Brown reflected on key points from the Symposium including: –

- the need for flexibility in sports hall design for types of use and income

- sufficient storage space for each activity area.

- separate changing accommodation for pool and sports areas.

- A suitable general sports hall environment without windows in the walls, with any ideally placed in the roof

- As robust and maintenance free as possible.

Finally, George Torkildsen highlighted consequent centre management issues, and the political and moral issues surrounding charges and costs to Local Authorities and trusts. However, there were as many design questions as answers in 1969! [At that time incidentally, there was a modest Technical Unit for Sport [TUS] located in the Department of Education and Science].

Reading the report of the Symposium now, it all seems somewhat naïve considering how centre design and operation has developed and become very sophisticated over the years, but these were very early, tentative technical steps in virgin territory.

The race was on at that time for designers to learn quickly and adapt. At this distance it may seem difficult to understand that one of the first problems for designers was the unknown number of users; the unforeseen response of users; and whether the proposed facilities and uses would succeed. During these early days the centre manager was often appointed during the building phase (sometimes earlier), as their sports experience was helpful to the sports detail. Over the years design patterns and procedures became more standardised and professional, thanks not least to The Sports Council’s considerable efforts and leading architects of the time (the TUS had by the 1970s become part of The Sports Council operation).

4) Special events, reports and publications on the design of centres: 1962-93

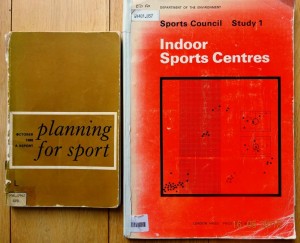

Key publications and events on sports halls and centres and their design and provision emanated from different organisations between 1969 and 1993. In the first half of the 1970s, three types of ‘influence’ were of particular note.

a. Sports Centres and Swimming Pools’, was commissioned and published in 1971 by the Thistle Foundation in Edinburgh and authored by Felix Walter FRIBA. It was a design study with particular reference to the needs of the physically disabled. As such, it was one of the first attempts to relate the sports centre concept specifically to people with disabilities. It recognized that the one of the greatest essentials in the social integration of people with disabilities, especially the wheelchair-bound, is access to public buildings. It highlighted the importance of external entrance by ramp, the advantage of ground floor facilities, and lifts to upper floors where necessary. Various aids for pool access were reviewed. Equally reception, changing and toilet facilities needed suitable designs. The study drew on various examples, particularly Bellahouston Sports Centre in Glasgow, which was one of the first centres to recognise such needs in its design. This may all seem obvious in the 21st century, but remember The Disability Discrimination Act did not become law until 1995 (now replaced by the Equality Act 2010). The Act led to many existing public buildings, including those for sport, leisure and entertainment, having to implement alterations to make them easily accessible for people with disabilities.

b. Design Conferences at the Universities of Newcastle upon Tyne (1971) and Exeter (1972) and in Nottingham (1975) There was growing interest, at that time, in all the detail of sports centres, from locational planning to design and operation. Seminars and meetings increasingly focused on these issues and the thirst for knowledge was great. All the regions of the UK held seminars on design and management issues in the 1970s and 1980s. An extensive report on the 1971 Newcastle seminar, organized by the CCPR on sports centre design issues, was published. Speakers included Peter McIntosh (‘value for money’ and ‘meeting social needs’); Ian Douglas (‘operations’ – Bellahouston & Bishopbriggs); George Torkildsen (‘evaluating needs’ and ‘deciding priorities’) and Harry Faulkner-Brown on design considerations (the architect of the Lightfoot Sports Centre, which opened in 1965).

Faulkner-Brown highlighted the importance of ‘controlling the environment’, which is always, he said, a product of compromises and establishing priorities. He highlighted in order of importance lighting; heating & ventilation; flooring; and sound. In an honest reflection, he said Lightfoot’s translucent roof was fine for football but a distraction for fast moving ball games (he highlighted how the Houston Astrodome’s glazed dome made it inadequate for baseball). Perhaps as an indication of the overall picture of design development at that time, when he spoke of flooring, he mentioned vinyl flooring on top of plywood (University of Kent), and wooden floors which were common, referring to the maple floor in Sunderland FC’s Washington training hall. Such was the uncertainty at that time that his prediction that outdoor artificial turf carpet (then starting its long trail towards G4 surfaces of today) would become the chosen indoor surface for most sports halls has not come to fruition (yet!). The Lightfoot, which survives today, was the first of very few UK ‘dome’ centres. It was an early example of experimentation and was built to satisfy a brief to provide the largest possible indoor space with the limited funds available. It succeeded in certain ways, despite it being a design compromise.

The Exeter conference in 1972 highlighted the start of more diversification in the type of centre being provided, and hence in designs. Dual use schemes were becoming more common and the need for different kinds of provision besides the large ‘district’ centre started to be recognized. There was also a focus on swimming pool provision. Pool issues covered included the size of pools, technical systems, changing and clothes storage, and operating costs.

In 1975 the construction industry, a commercial beneficiary of the advent of sports centres, organized a major 2-day conference in Nottingham on the design and construction of indoor recreation, sports and leisure centres. An exhibition accompanied the conference. It is no surprise to find that Ron Pickering, George Torkildsen, Harry Faulkner Brown and Gerry Perrin were amongst the speakers, alongside a range of technical experts. This was the most comprehensive event of its kind to be held to date, providing a detailed review of not only UK but also European experience of the design and operation of centres.

Professional journals, especially ‘The Architects Journal’ and ‘Building’, and local government magazines, reviewed the design and construction of some new centres in detail, including Harlow, Dunstable and Alton. This disseminated fresh information at the time. In 1983 The Sports Council published ‘Indoor Sport and Recreation Update’. This was a comprehensive compendium of sports centre reprints from The Architects Journal from that year. It included details of many centres, including Bury St. Edmunds; Northgate, Chester; Rushcliffe; South Tyneside; Worksop, Lea Valley; Hawick; Crawley, Bletchley, Warrington Spectrum; and Rhyl.

c. The NPFA published ‘Indoor Recreation Centres’ in 1972, based on centres so far developed. Again, Gerry Perrin led the study. “Past is the time when the idea of a sports hall has to be sold” it stated. Four types of centre were identified by the NPFA at that time: –

– Multi-sports (wet & dry centres) e.g. Crystal Palace, Bingham, Worksop, Carlton Forum, Folkestone and Aberdare.

– Dry sports centres + ancillary e.g. Harlow, Wallsend, Bracknell, Stockton, Bellahouston, Meadowbank, Ponteland and Redbridge + university halls

– Recreation centres + sport + arts e.g. Billingham Forum, Carlton Forum, Fort Regent (Jersey) and Canon Hill Park (Birmingham)

– Indoor sports centre – 2 or more sports halls + ancillary facilities.

(Refer to the Introduction – Defining the ‘UK Community Indoor Sports Centre’)

The value of the publication at that time was in reflecting on design lessons from the first centres. It highlighted, for example, how Harlow overcame clerestory window glare by applying anti-glare paint. Consequently, it noted that most new halls at that time were being fully lit artificially, which of course did lead to higher running costs. It also said that there was considerable scope for further research into low-cost mechanical services, especially for pools. The document also recognized the need for operational management input from the very beginning of centre design, and notwithstanding the value of the early appointment of managers, here we see one of the first references to the need for management consultancy. Later in 1974, we can see the development of different design and architectural solutions in another NPFA study, ‘Local Recreation Centres’. Here the focus was on provision for a much smaller catchment than the four types identified in 1972. Here the assessment of provision and design of facilities needed to reflect whether it was a discrete rural or urban neighbourhood (especially in new towns) and whether other welfare services could be embraced in the building. It quoted Killingworth (New Town) Communicare Complex as an example.

Alton SC 1974

Thus, three NPFA reports, these two, together with that in 1965, ‘Community Sports Halls’, provide a useful picture of how the design of centres rapidly progressed in the first ten years, alongside a more analytical and experienced approach to communities and users.

The direct link between research and design was highlighted in 1980. The Scottish Sports Council organized four national seminars on sports centres and swimming pools, following its ground-breaking research exercise – ‘A Question of Balance’. The Seminar ‘Design’ was held in December 1980 it pulled together design experiences to date and highlighted developments in energy conservation and pool purification systems, package deals and low cost centres, and the lack of clear briefs for architects.

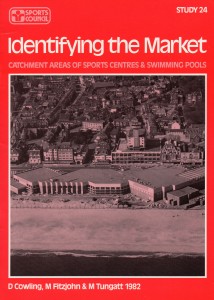

It is interesting that after a review of studies of the catchment areas of sports centres and swimming pools had started, Mike Collins quickly concluded that there was sufficient information for a suggested development process, which was added before publication in 1982. Reflecting this, the title became ‘Identifying the Market’. Mike was able to write in the Foreword, “Much research on sports facilities in the past has attempted to assess what has taken place; now we can distil this descriptive research into prescriptive”.

It is interesting that after a review of studies of the catchment areas of sports centres and swimming pools had started, Mike Collins quickly concluded that there was sufficient information for a suggested development process, which was added before publication in 1982. Reflecting this, the title became ‘Identifying the Market’. Mike was able to write in the Foreword, “Much research on sports facilities in the past has attempted to assess what has taken place; now we can distil this descriptive research into prescriptive”.

At national level the publication of ‘Sport in the Community…The next Ten Years’ in 1982 was the most significant strategic development by The Sports Council. Not surprisingly, the analysis behind the Strategy highlighted that growth in participation in indoor sports had doubled in the 1970s and recognised that “the mainspring of the growth in indoor sport has been the multi-sports centres”. However, it also recognised the conclusions from much of the research outlined above. “These [indoor multi-sport centres] are essentially local in their impact and introduce new people to sport without emptying existing facilities or damaging clubs. Where they are readily accessible and well marketed and managed, they attract a wider use by the local population”. But the Strategy went on to confirm many of the other research findings, noting that “there are groups which are low in participation – housewives, especially those with young children, semi-and unskilled workers, people over the age of 45, and the handicapped [sic], ethnic minorities and the unemployed”.

At national level the publication of ‘Sport in the Community…The next Ten Years’ in 1982 was the most significant strategic development by The Sports Council. Not surprisingly, the analysis behind the Strategy highlighted that growth in participation in indoor sports had doubled in the 1970s and recognised that “the mainspring of the growth in indoor sport has been the multi-sports centres”. However, it also recognised the conclusions from much of the research outlined above. “These [indoor multi-sport centres] are essentially local in their impact and introduce new people to sport without emptying existing facilities or damaging clubs. Where they are readily accessible and well marketed and managed, they attract a wider use by the local population”. But the Strategy went on to confirm many of the other research findings, noting that “there are groups which are low in participation – housewives, especially those with young children, semi-and unskilled workers, people over the age of 45, and the handicapped [sic], ethnic minorities and the unemployed”.