First and foremost

The first combined indoor & outdoor facility success story following the 2nd World War was the formation of the Harlow and District Sports Trust and the development of Harlow Sportcentre. Harlow led the way in the UK, with several other centres hard on its heels. The story of Harlow New Town had begun in 1947. In that year the Labour Government issued the designation order for a completely new planned community housing some 60,000 people to the west of an existing Essex village called Harlow. The designation order eventually led to the opportunity to develop Harlow Sportcentre.

As early as 1952 the Master Plan for the town had identified an area of approximately 30 acres for sports facilities, but as the town grew there was no agency or authority immediately available to develop the site. The town however was growing fast and by 1958 the population was over 40,000, with an exceptionally high percentage of children. In 1958, a small group of enthusiasts from the Harlow Industrial Sports Association met with Harlow Development Corporation to explore the possibilities of developing the designated sports area. The Corporation, unable to take on full responsibility, outlined the idea of a non-profit-making company with charitable status and suggested a Sports Development Council to pave the way. The group left agreeing to establish a Council representing sports people and organisations, industry, the professions, the Corporation and local authorities.

Harlow & District Sports Trust

From this Development Council emerged the Harlow and District Sports Trust, formed as a non-profit making company, registered as a charity, and representing a unique essay in co-operation between local and regional statutory and voluntary organisations. The overwhelming problem, however, was finance. Overall costs were estimated at over £200,000 and the work therefore had to be phased. Secondly, the burden would have to be spread and every effort made to encourage contributions from central Government sources, Local Education Authority, Local Authority, Development Corporation, sports interests and the local community.

Finance and construction

The first grant was from the NPFA/Wolfson Trust and this “primed the pump” and set the whole machinery in operation. A fundraising Supporters Club was formed. Encouraged by these efforts, the Trust proceeded with plans. Construction of the football and athletics arena and track got underway. Then the Development Corporation offered to construct the cricket and hockey ground. Plans for the indoor sports hall were already under discussion, but shortage of capital prevented an immediate start. Amidst a welter of construction, the activity programme of the Centre began to emerge. The programme that summer included Inter-County Athletics matches, Essex County Schools Finals, Southern Counties Women’s A.A.A. Championships and many local school and youth events.

In the meantime, there were negotiations with the Harlow Town Football Club, the Harlow Men’s and Women’s Hockey Clubs and the newly formed Stort Cricket Club for licences for them to use the grounds. In October 1960, the new club room and changing block were opened by Sir Stanley Rous, President of FIFA. The development of the programme of use was new territory for the UK. By the time the Wolfenden Report was published in 1960, Harlow, the first UK community sports centre, had been planned and opened its first facilities. In April 1961, the cricket ground was opened with a match between teams captained by England cricketers Peter May and Douglas Insole, and the newly formed Stort Cricket Club made its headquarters at the Centre. Despite limited facilities, the Junior Sports Club and the Youth Sports Association continued to grow and the total membership of the Centre had reached 700 by the end of that year.

Harlow – outdoor provision

To bridge that gap until the Sports Hall could be built and to relieve the pressure on the grass practice areas, the Trust took an urgent decision to develop the floodlit all-weather training area. This “Redgra” area was opened in October 1961 by Sir Stanley Rous and soon proved its great versatility and usefulness. In its first few months it was used to capacity by schools, juniors, and adult clubs. A dry ski-slope was also added. By this time 1,000 attendances at the Sportcentre were being recorded each week and an analysis showed that 70% of these were made by members under the age of twenty-one. Obtaining funding for a sports hall was a long, hard battle but grants and promises eventually started to come forward so the Trust decided to go ahead, even though it had a considerable sum to raise itself. Construction began in April 1961 and the sports hall opened in 1964. Historically this Sports Hall was the first in the UK to be completed for community use. The concept was therefore unique.

Leadership and Management

The Trust’s early good fortune had been to secure as its Chairman Colonel Arthur Noble, at that time Chairman of the Essex County Playing Fields Association, who guided and inspired this new venture from its inception. Already it was clear that leadership was the key to development, and here the Trust secured the services of George Torkildsen, a young P.E. specialist from one of the Harlow schools. George was appointed as the first UK sport centre manager, having taken up post on January 1st, 1961. Working almost single-handed, apart initially for a small team of voluntary helpers, he began to develop the use of the Centre.

George Torkildsen (1934 – 2005)

It was no easy task to integrate coaching and training into the programme of general use by members and clubs. This called for considerable skill and diplomacy on the part of the manager, youth leader and committees, and many valuable lessons were learnt. Harlow was a pioneering centre, not just for being first and managed by a trust, but for the pathfinder lead it gave in programming facilities and using the centre for sports coaching programmes. With George Torkildsen’s encouragement, outstanding coaches at the centre, Mitch Fenner (gymnastics) and Jack Kelly (trampolining), developed The Harlow Apex Club which produced national and international champions. The Centre was also a significant management training hotbed. In those early days, several young assistant managers, and recreation officers that the centre employed went on to become well-known managers at other centres across the UK.

UK impact

Harlow Sports Centre c.1965

The success of this pioneer centre encouraged many local authorities and other groups and bodies throughout the country to embark on similar schemes. Many came to study the lessons learned at Harlow. At one stage, there were visitors almost every day. The usual conclusion was that only local authorities could undertake schemes of such cost and complexity. Harlow’s experience demonstrated, even at that time, that the Trust system has many advantages. It combined stability within the flexibility needed if one is to experiment in new fields. Here it represented a unique partnership between statutory and voluntary bodies, leading to real involvement by the local community in both management and fundraising.

The critics who believed the scheme would prove a disaster had been confounded. The main problems arose from the intensity of use, day-long and year-round, and the cost of financing successive extensions in 1970 and 1975 to meet an ever-increasing demand. The centre could not have survived without the generous support of the local authorities. Harlow District Council subsequently replaced Harlow Development Corporation as the Trust’s principal benefactor, with Essex County Council paying for the use of its facilities by schools and other education groups.

Tonia Gosling

The Sportcentre served Harlow and district for over 50 years until 2010, when it was replaced by the new Harlow Leisurezone on a nearby site, as part of the Government’s Harlow Gateway Scheme.

Click through for (1) ‘The Middle Years’ – the reflections of John Wright, General Manager 1973-2005 and (2) ‘Harlow Leisurezone 2016’ by Tonia Gosling, General Manager.

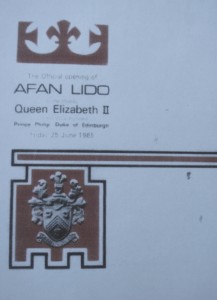

Afan Lido was partly influenced by tourism considerations and built on the seafront at Aberavon Beach, Port Talbot, adjacent to a large post-war housing development. It was more than just the first purpose-built sports centre in Wales. Given its range of facilities and the almost singular focus on sport elsewhere in the 1960s, it was probably the first true UK ‘leisure’ centre, ahead of Billingham Forum. Afan Lido was opened by the Queen on June 25th 1965, on a day when it rained so hard it was impossible to go outside! The Lido was the first modern building of its type in Wales. It represented the beginning of a new age and was seen very much as a Welsh turning point. In those days Port Talbot was a prosperous town – the steelworkers were very highly paid and the Lido was a symbol of that new industrial prosperity, and of key importance to the local economy.

Afan Lido was partly influenced by tourism considerations and built on the seafront at Aberavon Beach, Port Talbot, adjacent to a large post-war housing development. It was more than just the first purpose-built sports centre in Wales. Given its range of facilities and the almost singular focus on sport elsewhere in the 1960s, it was probably the first true UK ‘leisure’ centre, ahead of Billingham Forum. Afan Lido was opened by the Queen on June 25th 1965, on a day when it rained so hard it was impossible to go outside! The Lido was the first modern building of its type in Wales. It represented the beginning of a new age and was seen very much as a Welsh turning point. In those days Port Talbot was a prosperous town – the steelworkers were very highly paid and the Lido was a symbol of that new industrial prosperity, and of key importance to the local economy.