8.2.6 The advent of ‘local’ and ‘national’ Not for Profit Distribution Organisations (NPDOs – Trusts)

- The attraction of trust arrangements

By the turn of the 21st century asset-owning amateur sports clubs were facing increasingly difficult financial circumstances. They argued that their role provided substantial ‘community benefits’ that ought to be recognised by government and given financial support. This lobbying resulted in changes to charity law whereby ‘community sport’ was recognised as a charitable objective for the first time. Consequently, community sports organisations could organise their affairs in such a way as to achieve charitable status and, with that, significant financial benefits such as reduced NNDR. An unforeseen consequence of CCT was that some local authorities thus saw the opportunity to reduce their costs by operating their sports facilities through a charitable trust. Such a trust also operates outside of CCT legislative requirements, provided the rules on limiting Councillor governance in the Trust are met.

Whether the charitable Trust operates the sports facilities with its own directly employed staff or whether the Trust contracts out all or part of the operation is a matter for the charity to decide. The decisions of the charity are subject to the scrutiny of the Charity Commissioners particularly in relation to accounting, value for money and any conflict of interest amongst Trustees.

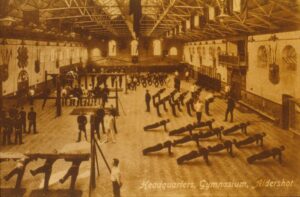

However, as the contracting process progressed, the initial advantages of a private contractor, which may have been viewed as mainly or exclusively financial, came to be balanced against actual or perceived disadvantages. The completion of ’Options Appraisals’, stimulated by the broader Government Best Value approach, led many local authorities to consider and pursue the trust route by establishing a Not for Profit Organisation (NPDO) to operate their centres (Sport England has published Options Appraisal Guidance – 2017). Coincidentally, such charitable structures, whether a Company Limited by Guarantee, a Public Interest Company (PIC) or an Industrial Provident Society(IPS), harp back to the start of some sports centres trusts mentioned in the 1960s and 1970s (indeed, charitable trusts have been running some public gyms and swimming pools since the 1930s).

In summary the basic and key features of trust management are:

- Responsibility for the management of the leisure facilities is transferred to a trust, usually with a contract and specification for services

- The trust would typically be a registered charity with a board of voluntary trustees and is independent of the Council

- The Council would lease any facilities to the trust and would typically provide an annual grant to the trust, reflecting the likely operational subsidy of the facilities

- In many cases, any staff employed to manage and supervise the facilities would be employed directly by the trust under TUPE regulations

- The trust undertakes the management of the facilities, gathering all income generated by the facilities and being responsible for most costs incurred by the facilities

- Typically, the Council retains ownership of the building and some responsibilities (usually in respect of structural repairs and maintenance) and incurs costs in respect of these responsibilities. The operating risks of the service would transfer to the trust.

- A Charitable Trust is able to access 80% mandatory NNDR relief. The remaining 20% is discretionary relief that the Council has the option to grant. Of the discretionary relief the Council pays 75% and the government 25%, thus saving the Trust NNDR expenditure. The Council should gain from the consequent operational savings made by the Trust.

George Torkildsen, one of the architects of the first Trust in Harlow, described trusts as having “structural adaptability to succeed. They benefit from fund raising opportunities, rate relief and tax advantages”.

As the 21st century proceeded, more and more local councils, both those that had not awarded contracts to private companies, and those that had, opted to set up local NPDOs with charitable ‘trust’ status. This became known as the ‘third way’ (one of Prime Minister Tony Blair’s favourite expressions) alongside the other two options of direct management and a private operator contract. NPDOs now often arise as a result of a Council’s ‘options appraisal’ process. Originally such trusts were set up by individual local authorities with the intention of securing local accountability and input to the management of their local facilities. This system meant that the local council, which had established them, often took a paternalistic approach to the trust. Councils of various political complexions viewed trusts as ‘arms-length’ private operations.

As they and the market developed some local trusts sought to expand their geographical scope by partnering with another Council or simply bidding for available contracts. It was in this way that Freedom Leisure, established as Wealden Leisure Ltd to solely run the facilities for Wealden DC, expanded over two decades to become a national player. Some national trusts have formed a small number of partnerships for specific projects. Freedom Leisure, for example, formed a 10-year partnership in 2011 with GLL in support for the Guildford contract.

The validity of leisure trusts to operate as charities was clarified in 2004. The Charity Commission considered and approved applications from Trafford Community Leisure and Wigan Leisure and Culture Trust to register as charities. The Commissioners were satisfied that the Trusts were both sufficiently independent and concluded that they are established for exclusively charitable purposes. The key factors were, and remain, the independence from the respective councils and the extent to which they could be charities if carrying out statutory duties imposed on governmental authorities. (For more details see Leisure Trusts – The reasons, the models and the benefits by Hywel Griffiths).

- The private companies respond to local trusts

Everyone Active Westminster

When councils started to establish ‘local’ NPDO trusts, the major operating companies changed their legal structures to charitable trusts to match the various advantages, and have gone on to tender successfully as charities, with all the same advantages as the local trusts. These trusts have been referred to as ‘mega trusts’. Some large councils with a wide range of extensive facilities were able to create quite large trusts. These larger trusts generally seem the most stable and sustainable. What is emerging is that some of the shortcomings of small local trusts, especially in respect of investment, are beginning to prove disadvantageous. In the last few years, a number have succumbed to takeover by one of the ‘national’ trust operations. For example, North Country Leisure Ltd and Carlisle Leisure Ltd, both smaller trusts, were merged with GLL by 2015.

Concerns and issues have been raised about the national ‘mega’ trusts. One early concern was the ethics and legality of the change from private companies to trusts, whilst protecting director and manager salaries. However, both the Government and Charity Commission seem satisfied with the changes. Other concerns have included operational issues. For example, GLL had significant problems with the unions when taking over the Belfast centres and the Unite Union has a standing disagreement with GLL over zero hours contracts and union representation. There is also a concern that one size fits all national ‘branded’ services, especially for Gym memberships, may not always be appropriate in all local circumstances.

- Trusts abound and have some collective strength

The leisure trust movement has developed an organisation to represent the interests of all trusts, large and small. Community Leisure UK (previously SPORTA) has over 110 trust members, roughly 85% of the UK total. This indicates that there are at least 100 ‘local’ trusts operating the length and breadth of the UK in 2020. All the local trusts are prominent players on the sport, fitness and health scene in their localities. As there are so many it may seem invidious to mention examples, but these few current examples of ‘local’ trusts are representative of the many across the country: –

The leisure trust movement has developed an organisation to represent the interests of all trusts, large and small. Community Leisure UK (previously SPORTA) has over 110 trust members, roughly 85% of the UK total. This indicates that there are at least 100 ‘local’ trusts operating the length and breadth of the UK in 2020. All the local trusts are prominent players on the sport, fitness and health scene in their localities. As there are so many it may seem invidious to mention examples, but these few current examples of ‘local’ trusts are representative of the many across the country: –

- Kirklees Active Leisure – since 2001 KAL has managed 13 leisure facilities and swimming pools on behalf of Kirklees Council (includes Huddersfield).

- Excite (West Lothian Leisure) runs 10 venues – a social impact study in 2011 showed that Excite’s work was generating health-related benefits worth almost £17M.

- Live Active Leisure, Perth (one of the oldest leisure trusts operating since the early 1970s (Bells Centre).

- Life Leisure (now Aneurin Leisure) has provided leisure services in Blenau Gwent since 2014.

- Pendle Leisure Trust operates centres in the Pendle District of East Lancashire. The Trust is responsible for operating three leisure centres, a spa, golf course, an athletics and fitness centre, a theatre and an arts, culture and enterprise centre.

- Active Northumberland manages a range of leisure and cultural facilities across the county including: swimming pools and leisure centres; sports facilities; and tourist attractions such as heritage sites, arts’ centres, and parks and gardens.

- LED Community Leisure runs 16 leisure centres across Devon and Somerset.

- Magna Vitae Leisure & Culture Trust was established in 2016 for East Lindsey District.

New provision and indeed major refurbishment has become very much tied to the longer-term involvement of the new breed of trust management organisations through contracts which seek to set outcome parameters but allow scope for the Trusts to achieve financial growth which is ploughed back into their operations. This can be more difficult for the smaller trusts. ‘The Move Towards a Trust’ sets out the kind of process that a number of councils have adopted in creating a local trust.

An RBS/NatWest Report in 2014 highlighted the largest leisure trusts by turnover in 2012/13 as: –

- GLL – £123M

- Edinburgh Leisure – £29.7M

- Kirklees Active Leisure – £12.6M

- Live Active Leisure (Perth) – £10.5M

The scope of what have become known as the ‘mega trusts’ has increased considerably as time has gone on. Surveys in April 2015 of 232 local authority websites showed how the transfer to larger trusts has grown. Nine ‘national‘ operators (the majority as NPDOs) managed facilities in 44% of authorities. 144 of those transferred to larger operators, who were defined as those operating in five of more local authorities. A further 21 local authorities transferred to regional operators, defined as those operating in more than one local authority but in less than five. The remaining 67 local authorities have their leisure facilities managed by a local operator who only manages leisure facilities in that local authority area. 26 local authorities had a position where two different external operators operated within an individual local authority area. Of 161 contracts three operators held 61%. The majority of those operated as Not for Profit Distributing Organisations. At that time half of local authority leisure provision was managed by nine leisure operators.

In 2019/20 the approximate number of contracts held by each of the national ‘mega’ trusts is given below: –

Trust

|

2019/20 Approx contracts

|

| Everyone Active (SLM) |

160 sites |

| Places Leisure |

102 |

| 1forLife |

40 |

| GLL |

270 |

| Parkwood |

100 |

| Freedom |

84 |

| Fusion |

80 |

By around 2020 at least 50% of local authority facilities were operated by some form of trust, with two-thirds by charitable trusts and one-third by mutuals (e.g. an Industrial Provident Society).

- Strategic impact of trusts

Regardless of political standpoints, there can be little doubt that today sports and leisure centres are providing substantial community benefits for less cost than in the past. Trust arrangements and benefits are more complex than simply the financial outcome, even if that is important. Research of one trust published by Gavin Reid (Managing Leisure – Taylor Francis Online) found that “the trust investigated benefited from an enhanced leisure focus and the combination of a ‘business-like’ approach and public sector ethos to produce: £2 million investment in facilities; a substantial reduction in council subsidy; reduced staff absenteeism; and a cultural change that extended middle managers’ decision-making responsibilities to generate greater service ownership and customer focus. In addition, the knowledge and experience of those invited onto the trust’s board of management provided quicker and better decisions more applicable to the prevailing leisure industry. However, the trust had not realised its “third way’ potential because the council didn’t appreciate the wider implications of New Labour’s modernizing agenda. Its prime concern was with the pragmatic (financial) benefits from externalizing leisure facilities, rather than extensive strategic thought about the nature of the new organization being created, its environment, or role in the local area. This led to decisions that mitigated against a joined-up service”.

Many smaller trusts have appreciated the broader issues and benefits in the way that they operate. This is reflected in their overall leisure programmes, especially if their contract brief also goes beyond centres, as many do. They see themselves as social enterprise leisure companies focusing on quality with a commitment to inclusivity within local communities. It remains to be seen, from substantial research (hopefully underway) whether all the changes since the 1980s have improved or decreased the broad social impact sought by the early centres. The divisive effect of CCT was noted earlier. Some tension occasionally exists in the current trust era between council officers (and Members) and trust officials, where in some cases trust officials are former council colleagues and are now able to exercise perhaps greater freedom. Also, individuals involved in their initial establishment may change and some of the original purposes for the decision to create the Trust may be forgotten or misunderstood.

The impact of all the organisational changes over the last 40 years has inevitably impacted on the professional management scene. The sterling work of ILAM and its successors, up to and including CIMSPA today, have assisted in overcoming such professional challenges.

- Trust management – the argument and issues

Despite the advantages and the surge of new trusts, there continue to be some arguments about their use and development. The national ‘mega’ trusts are most at the focus of any issues, although objections are raised regarding local trusts from time to time, often from a political viewpoint. We have mentioned some continuing concerns of unions and the increase in the number of small trusts being taken over by the ‘mega’ trusts. The scope of control nationally by GLL, with now in excess of 270 contracts, and just seven ‘national’ trusts running 850 sites, has not gone unnoticed. The Case Against Leisure Trusts (a European Services Strategy Unit Paper – July 2008) delivered a critique highlighting failures and potential drawbacks. Other critics have been the Directory for Social Change that has argued that trusts lack true independence and fail to conform to the public’s ideas about charity.

- Personal reflections and experiences

Personal reflections on trust developments have been provided by: –

Jeff Hart, founding Managing Director, Freedom Leisure – A Personal Reflection.

The Management and Growth of Leisure Trusts – Sheridan Easton and Paul Wheeler (including experiences at Brentwood DSO, and Test Valley Leisure Ltd).

- Trusts continue to dominate the centre scene

In 2020 we can see that the contracting picture for sports and leisure centres has changed dramatically, with a ‘tsunami’ of changes since the legislation for CCT in 1989 and its implementation from 1992. The current picture remains complicated, still somewhat uncertain, but more mature in all senses. As we see in Chapter 10, the management of centres by trusts, large or small, continues to dominate the sports centre scene in the 21st century.

In 2020 we can see that the contracting picture for sports and leisure centres has changed dramatically, with a ‘tsunami’ of changes since the legislation for CCT in 1989 and its implementation from 1992. The current picture remains complicated, still somewhat uncertain, but more mature in all senses. As we see in Chapter 10, the management of centres by trusts, large or small, continues to dominate the sports centre scene in the 21st century.

For more detailed information about various trusts see Leisure Trusts – The reasons, the models and the benefits (H. Griffiths) and Trusts for Big Society (Winkworth Sherwood Solicitors).

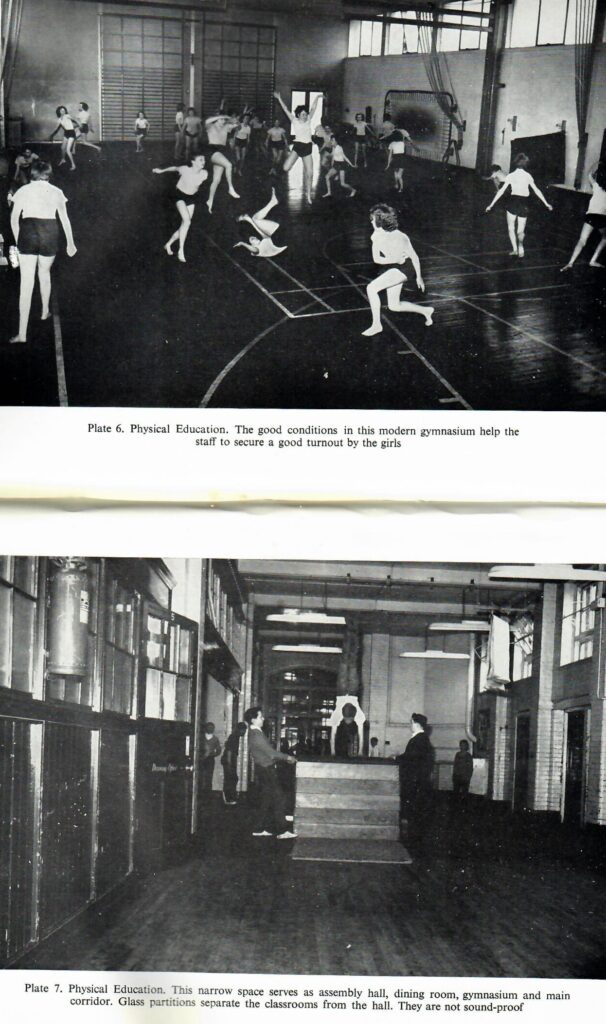

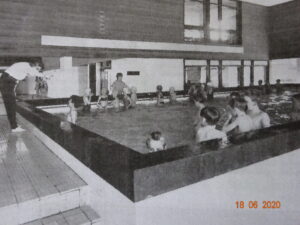

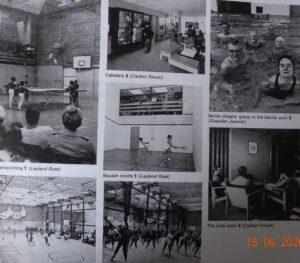

The role of school-based indoor sports facilities was first given special importance in 1964. In the wake of the Wolfenden Report, the Joint Circular ‘Provision of Facilities for Sport’ [DES 11/64; MHLG 49/64 and Scottish Education Department Circular No. 550 ‘Facilities for Recreation’] had emphasised the desirability of dual use (education and public) and joint provision of facilities by two or more partner authorities. It drew attention to the possibilities of obtaining better value for money by combining educational funds with other local authority or voluntary sources to provide sports facilities for use by both pupils and the general public.

The role of school-based indoor sports facilities was first given special importance in 1964. In the wake of the Wolfenden Report, the Joint Circular ‘Provision of Facilities for Sport’ [DES 11/64; MHLG 49/64 and Scottish Education Department Circular No. 550 ‘Facilities for Recreation’] had emphasised the desirability of dual use (education and public) and joint provision of facilities by two or more partner authorities. It drew attention to the possibilities of obtaining better value for money by combining educational funds with other local authority or voluntary sources to provide sports facilities for use by both pupils and the general public. The early circulars, the House of Lords Report (1973), the 1975 White Paper, ‘Sport and Recreation’, and

The early circulars, the House of Lords Report (1973), the 1975 White Paper, ‘Sport and Recreation’, and

Apart from community recreation benefits, it was also expected that pupils would benefit and the ‘gap’ between school and adulthood that Wolfenden identified could be tackled. A five centres study by Prescott-Clarke and Grimshaw in 1977 showed that school leavers are encouraged to continue participation in activities by the wider range of programmes at schools with community leisure centres. However, it was also surprising how few school leavers participated at the centres after leaving school, at some centres as little as 10%. ‘Half Our Future’ was a Report of the Central Advisory Council for Education (England) in 1963, on the education of pupils aged 13 to 16 of average and less than average ability. It carried an ironic quote –

Apart from community recreation benefits, it was also expected that pupils would benefit and the ‘gap’ between school and adulthood that Wolfenden identified could be tackled. A five centres study by Prescott-Clarke and Grimshaw in 1977 showed that school leavers are encouraged to continue participation in activities by the wider range of programmes at schools with community leisure centres. However, it was also surprising how few school leavers participated at the centres after leaving school, at some centres as little as 10%. ‘Half Our Future’ was a Report of the Central Advisory Council for Education (England) in 1963, on the education of pupils aged 13 to 16 of average and less than average ability. It carried an ironic quote –

The second precedent was the youth wings added to many schools from the early 1960s in the wake of the

The second precedent was the youth wings added to many schools from the early 1960s in the wake of the

In the mid to late 1990s the consequences of the CCT legislation in relation to sports and leisure facilities varied significantly around the country. The private sector had its ups and downs and did not develop as much as in other defined activities such as refuse collection and grounds maintenance. Both private and public sectors had to devote significant time and resources to adhering to the CCT requirements.

In the mid to late 1990s the consequences of the CCT legislation in relation to sports and leisure facilities varied significantly around the country. The private sector had its ups and downs and did not develop as much as in other defined activities such as refuse collection and grounds maintenance. Both private and public sectors had to devote significant time and resources to adhering to the CCT requirements.

The leisure trust movement has developed an organisation to represent the interests of all trusts, large and small. Community Leisure UK (previously SPORTA) has over 110 trust members, roughly 85% of the UK total. This indicates that there are at least 100 ‘local’ trusts operating the length and breadth of the UK in 2020. All the local trusts are prominent players on the sport, fitness and health scene in their localities. As there are so many it may seem invidious to mention examples, but these few current examples of ‘local’ trusts are representative of the many across the country: –

The leisure trust movement has developed an organisation to represent the interests of all trusts, large and small. Community Leisure UK (previously SPORTA) has over 110 trust members, roughly 85% of the UK total. This indicates that there are at least 100 ‘local’ trusts operating the length and breadth of the UK in 2020. All the local trusts are prominent players on the sport, fitness and health scene in their localities. As there are so many it may seem invidious to mention examples, but these few current examples of ‘local’ trusts are representative of the many across the country: – In 2020 we can see that the contracting picture for sports and leisure centres has changed dramatically, with a ‘tsunami’ of changes since the legislation for CCT in 1989 and its implementation from 1992. The current picture remains complicated, still somewhat uncertain, but more mature in all senses. As we see in Chapter 10, the management of centres by trusts, large or small, continues to dominate the sports centre scene in the 21st century.

In 2020 we can see that the contracting picture for sports and leisure centres has changed dramatically, with a ‘tsunami’ of changes since the legislation for CCT in 1989 and its implementation from 1992. The current picture remains complicated, still somewhat uncertain, but more mature in all senses. As we see in Chapter 10, the management of centres by trusts, large or small, continues to dominate the sports centre scene in the 21st century.